Why Blacklisting Is Harder Than You Think.

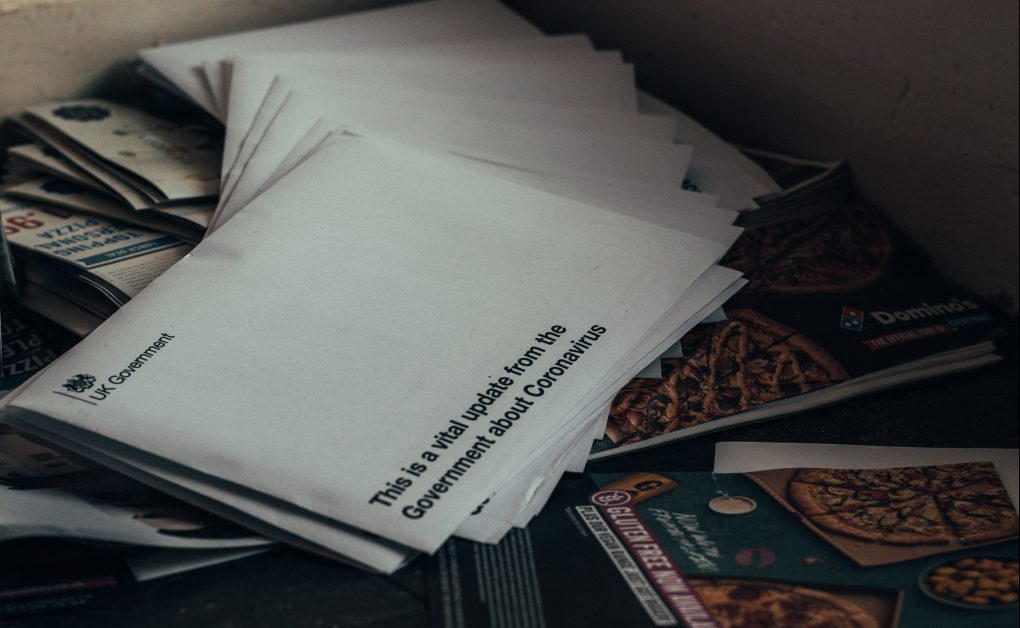

Sadly, we don’t have to look far to find examples of suppliers being accused of illegality. The Grenfell enquiry heard evidence that suppliers sold products that they knew “were dangerous to life” . McKinsey is being asked by a parliamentary committee in South Africa to answer for payments made to a firm controlled by the Guptas, and there’s a wealth of misdemeanour associated with Covid-19 , including sufficient concern about the UK’s PPE procurement to trigger legal challenges. Even EY has been the subject of scrutiny from Spotlight on Corruption, and a call made for an outright ban from public sector contracts.

These demands are likely to become more urgent as more governments launch inquiries into procurement during the pandemic, inevitably evidence of poor behaviour by suppliers will emerge.

What can governments do to black list suppliers and how effective is any preclusion? This is the point where we have to stress that we’re not lawyers, so we’re not providing legal opinion here, just a view of the options facing the Government.

Blacklisting a company is relatively easy for governments to do. Nominally, all they have to do is detail the company that it considers should be exempted from future competitions and then issue guidance that public authorities cannot consider these companies when awarding public contracts. It is broadly as simple as announcing a policy.

The problems arise when that policy rubs up against a range of existing laws. In the EU no ban can contravene laws on restraint of trade, for instance the ban must protect the Government’s own interest but should not impact other, legitimate businessess being conducted by the supplier. This makes it very hard to publish a list of companies that have been blacklisted, as it is likely to impact the rest of a company’s business. Equally, naming and shaming company directors who have committed misdemeanours may contravene their human rights, for example, any right that grants someone a peaceful life.

Bans also need to consider how a supplier gets to demonstrate that they have reformed, so there should a clear lifting of a ban, either by time limit, or detailed corporate policy or process changes. Neither the duration of a ban, nor the requirements to life the ban can infringe other corporate or personal rights. For instance, in the EU, a government can’t insist that a director resigns or that a subsidiary is sold.

Governments also need make sure that the ban has some impact beyond just saying that company is banned. For instance, should a ban extend across a group of companies? Does a ban for poor practice in the audit function of a consultancy extend to a strategy practice too? Does the ban extend to directors? What happens if these people leave the business, or if the banned company closes? What if the directors resign, fold the company and start a new company? Should the ban extend to their new company? If so, on what grounds?

In summary, if a government bans a supplier, it mustn’t impact the other areas of their business, it can’t contravene employees’ human rights and it has got to give the firm a route back to trading fairly. As well as doing this it still has to implement something that has a meaningful impact, which can’t be side-stepped by some fleet-of-foot corporate restructuring.

Given what is stacked against governments looking to ban suppliers, it is hardly surprising that most look for other mechanisms to punish suppliers. In the UK in recent years we’ve seen some suppliers voluntarily ‘take a break’ from bidding into the public sector, as a way of demonstrating their own penance. However, this does require a level of both self-awareness and some sort of willingness to publicly admit failure.

To discuss with us our government procurement data products and services get in touch.